Originally published on The Conversation, as part of the Democracy Futures series

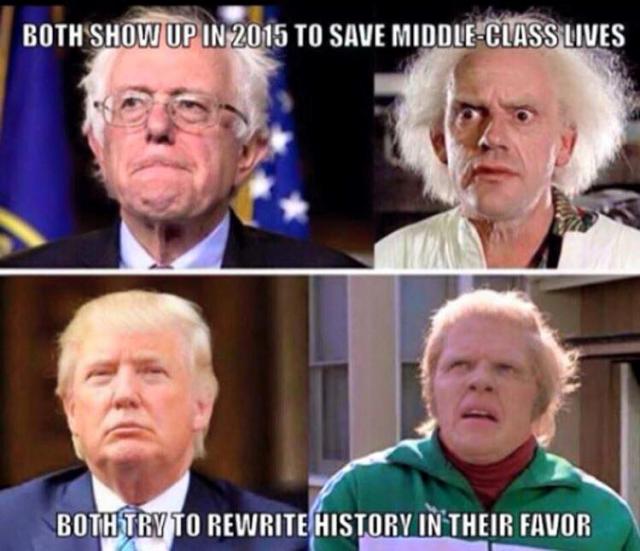

Log on to Facebook or Twitter and you’re likely to see a deluge of political posts – a humorous meme or viral video skewering politicians like Donald Trump, the latest hashtag slogan in response to breaking news, maybe even a social movement symbol as an updated profile picture.

The sharing of political opinion on social media is now ubiquitous. But what does it mean for democracy?

For years, debate has raged about the significance of symbolic, expressive political activity at the level of the everyday citizen.

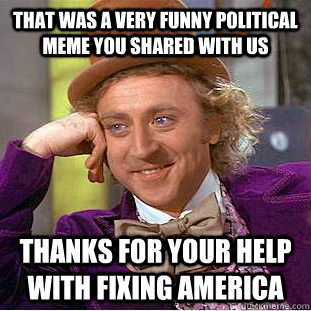

Critics fear it is simply self-satisfying “slacktivism”. It gives people an easy way to feel they’re contributing to a cause while substituting for more intensive political participation.

Conversely, optimists see a flourishing of civic engagement on the internet that gives people an accessible entry point into politics. If it helps them to develop a sense of political identity and agency, that enables more participation down the line.

These contrasting positions both have merit. Yet are those who take them asking the right questions in the first place?

By evaluating online political expression only in terms of possible impacts on traditional political activity, we risk sidestepping a far more crucial set of issues.

Forget ‘slacktivism’

Myriad organisations and institutions see this citizen-level expression on social media as being far from just a private or personal affair. It is increasingly valued for its aggregate promotional power. The marketing professions know this as electronic word of mouth.

Political groups of all stripes promote social media participation to amplify the reach and credibility of their persuasive messages. Although each individual act of posting, linking, commenting and liking may look insignificant up close, at a macro level they add up to nothing less than the networked spread of ideas.

There is enormous power here for mass persuasion, one viral share at a time. We dismiss this power at our peril.

During the 2016 US presidential election cycle social media soared to new heights of prominence in the political media landscape. It appears we are finally starting to recognise this power for what it is.

For instance, controversy over fake news on sites like Facebook has drawn attention to how peer-to-peer sharing can influence public opinion and even the course of elections (in this case by spreading false and defamatory messages about Hillary Clinton that consolidated her image problems). New research has highlighted how:

… far-right groups develop techniques of ‘attention hacking’ to increase the visibility of their ideas through the strategic use of social media, memes and bots.

The so-called alt-right celebrates its “meme magic” in propagating white nationalist ideology online in service of Trump. The pro-Clinton “Correct the Record” political action committee admits to paying people to post on social media during her primary battle with Bernie Sanders. We are seeing the persuasive value of citizen-level political media coming into sharp focus.

We need to reflect on how we each use this power. That involves thinking through the consequences of what we share online and how it can both strengthen and harm democratic values.

The citizen marketer

Sharing political opinion on social media must be understood in no small part as participation in political marketing. Its practitioners have long circulated persuasive media messages to shape the public mind and influence political outcomes.

This understanding calls for a new kind of media literacy. It requires individuals to acknowledge their own position in circuits of media influence and take seriously their capacity to help shape the flow of political ideas across networks of peers.

We should no longer think of political marketing — or its conceptual forebear, propaganda — as something only powerful elites do. We must recognise that we are all now complicit in this process every time we spread political messages via media platforms that we personally control.

Many citizens are keenly aware of their capacity to persuade their peers through their online posting. They have embraced the role of social media influencer. Most often, they focus on trying to rally the like-minded or undecided, rather than winning over converts from the other side.

This citizen marketer approach to political action can be seen as an outgrowth of the more established concept of the citizen consumer. A citizen consumer deliberately uses their spending power as another way to influence the political sphere.

They may, for instance, buy only environmentally friendly products, or boycott companies whose CEOs donate to campaigns and causes that the consumer opposes. Similarly, we are seeing citizens use their power as micro-level agents of viral media promotion and word-of-mouth endorsement to advance a wide range of political interests and agendas.

There is an enormous opportunity to democratise the flow of political media messages and publicise causes that lie outside the mainstream.

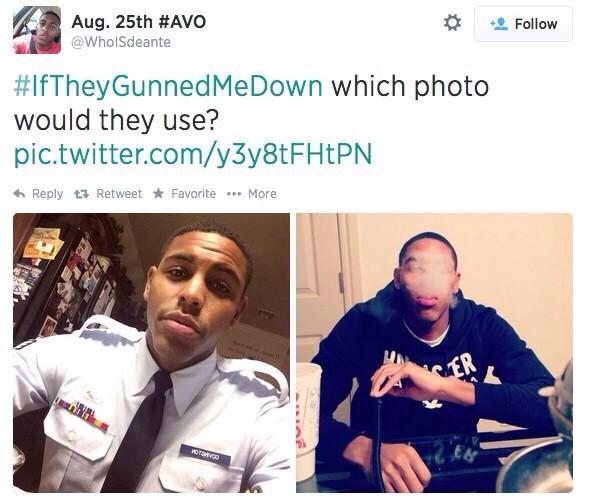

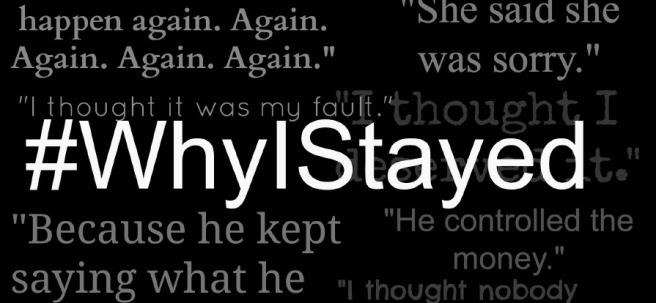

Consider recent activist movements, often built around viral hashtags like #occupywallsteet and #blacklivesmatter. Here, citizens are co-opting the tools and logics of social media marketing to advocate for political ideas that are typically poorly represented in the corporate mass media.

By recognising the potential value of our own grassroots political marketing power, we can gain a foothold in a political media landscape that elite interests traditionally dominated.

Perhaps even more importantly, cultivating a sense of responsibility for what we share on social media puts us in a better position to navigate the emerging digital ecosystem in which these elite actors are capitalising upon — at times even exploiting – our electronic word of mouth.

Know what you are posting, and who you are posting for

Nowadays, major election campaigns and large-scale issue advocacy organisations have professional digital marketing teams. One of their tasks is to spur the promotional labour of everyday citizens to maximise the virality of their messages, whether these people are truly aware of their participation in political marketing or not.

In addition, for-profit political news sites like Breitbart and The Daily Kos have become dependent on social media shares to boost clicks and advertising revenue, as well as to advance their proprietors’ often-partisan agendas.

In this environment, it is crucial that we make informed decisions when we lend our promotional labour and word-of-mouth endorsement to institutional actors and the interests and agendas they represent.

At times we may be eager to act as “brand evangelists” for candidates, parties, advocacy groups or news agencies whose political goals align with our own. At other times developing media literacy might cause us to pause and reflect before we amplify the latest trending political message.

Back in 2013, Facebook users posted a red equal sign as their profile picture to express their support for same-sex marriage. Some had no idea the symbol was the logo of the Human Rights Campaign. This organisation has had a controversial status in the LGBT movement because of its past treatment of transgender issues.

Would these citizens still have posted the image if they knew they were participating in a viral marketing campaign for an organisation that was not universally supported by the LGBT community, and whose message of equality has drawn criticism for emphasising assimilation over radical structural change?

Or would they have chosen instead to amplify an image and an organisation with a different shade of meaning?

These kinds of important conversations can only be opened up if we start to develop a critical literacy of the citizen marketer approach and how it is transforming what it means to be an active participant in our media-dominated, postmodern political reality.

If we see our online political expressions as mere “slacktivism”, a simple private matter, or just having fun with friends, then we become more vulnerable to manipulation by forces that seek to exploit our citizen marketing power to serve agendas that we may not share.

If we become more aware of our position in these circuits of power, we will be better equipped to resist this manipulation.