A few weeks ago, the Washington Post published an excellent piece about the phenomenon of Black Twitter, explaining how this community has used peer-to-peer social software to mobilize around numerous race-related political causes. Recently, Black Twitter activists have enjoyed a number of high-profile successes, such as pressuring a book publisher to drop a deal with a Trayvon Martin murder trial juror, pressuring InterActive Corp to admonish (and eventually fire) a PR executive who tweeted a racist joke, and pressuring singer Ani DiFranco to cancel an event at a former slave plantation. As these examples demonstrate, the political power of this form of activism rests in its high-profile application of public pressure. While tweeting responses to troubling news of racism and racial insensitivity may not “do” anything political in and of itself, it can put a media spotlight on an issue that may in turn lead to real change.

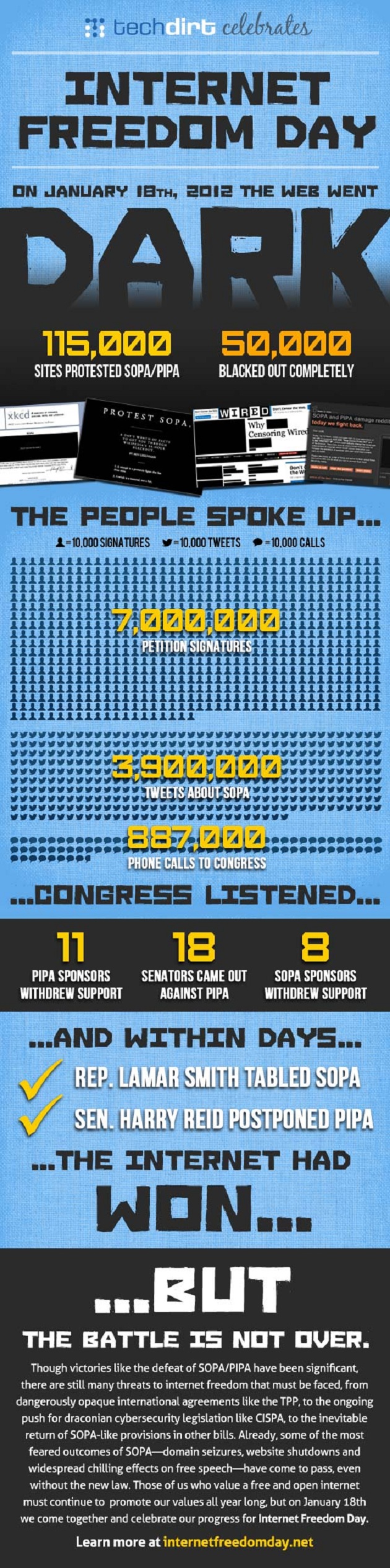

For many decades, professional watchdog organizations (AKA “pressure groups”) like the NAACP, GLAAD, and NOW have engaged in this form of activism to varying degrees of success. Now, it appears that decentralized groups of citizens are taking it upon themselves to band together around common issues and draw the public’s attention to them through strategic media interventions. The fact that Black Twitter has no organizational center, but is rather an open-ended community of like-minded citizens who find one another via popular hashtags like #PoliticosBlackIntellectuals #solidarityisforwhitewomen, is quite significant. It reminds me a lot of W. Lance Bennett and Alexendra Segerberg’s point that the traditional collective action of organized social movements is giving way to “connective action,” which describes a more diffuse and personalized style of public engagement that is powered by digital peer-to-peer networks.

That being said, there does appear to be a certain cohesiveness to virtual communities like Black Twitter, even though they are strongly decentralized. It is important to keep this point in mind when thinking about how political causes “go viral” on Twitter and social media platforms in contemporary times. When we say that a political news story, photo, or video “goes viral,” it conjures up images of widespread social popularity that does little to specify the investments and agendas of particular groups that have strategically contributed to the peer-to-peer spread of content. Communities like Black Twitter are essentially issue publics that draw upon their ranks to deliberately make a story like the Ani DiFranco concert or the PR exec’s racist tweet go viral – in other words, their viral popularity doesn’t just materialize out of thin air (i.e. from the aggregated effect of isolated, individual shares), but is rather the result of a concerted effort on the part of groups of invested citizens who wish to make an impact on the public sphere. Clearly, the agenda-setting labor of these viral pressure groups is a crucial object of study for scholars who seek to understand the emerging shape of digital activism.