As 2014 draws to a close, it seems destined to go down in history as a breakthrough year for the political hashtag. Of course, we’ve seen numerous examples of this phenomenon in the past, but in 2014, hashtag campaigns dominated political discourse on social media (and beyond) and reached a whole new level of prominence. Last year, it was the profile picture that emerged as a central locus of digital-era political expression, from the red equal signs for marriage equality to the Trayvon Martin-inspired blackout campaign. This year, however, hashtag campaigns were the story for viral politics. I’m not just talking here about the use of hashtags to classify, coordinate, and publicize broader political movements, which has been popular on platforms like Twitter for quite a while now (#OWS, #arabspring, etc.). Rather, what solidified in 2014 was the widespread use of hashtags as political memes in their own right, complete with a set of corresponding actions for each participant to take in the course of spreading endless variations on a theme. In other words, the hashtag emerged not just as a tool for online political mobilization, but also as a distinct advocacy tactic.

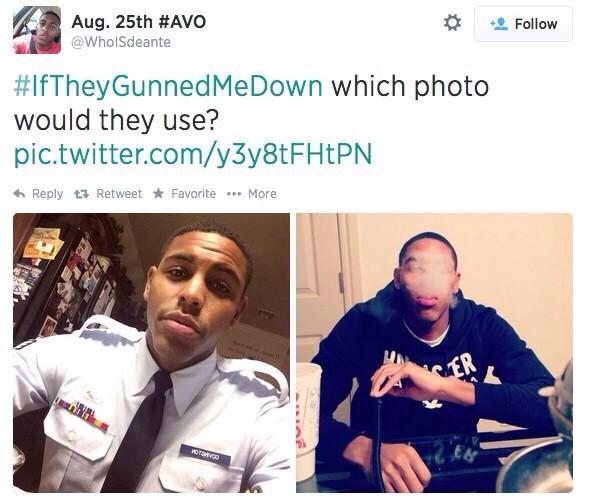

To illustrate the delineation I’m making here, let’s consider the most significant viral politics story of the year (at least in the United States): the online-fueled movement to protest the police killings of unarmed black civilians like Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Over the course of the year, many different hashtags were connected to this movement, from the catch-all #blacklivesmatter (which came to function as both the movement’s de facto name and its key rhetorical rallying point), to emotionally-charged references to the Brown case (#handsupdontshoot) and the Garner case (#icantbreathe). As they trended, these hashtags were mostly used within the movement as rather traditional political slogans, originating on Twitter and migrating to offline venues of protest like hand-held signs and T-shirts. However, it was another hashtag, #iftheygunnedmedown, which highlighted the use of the hahtag for distinctly participatory digital advocacy. The behavior, or instructions, for the #iftheygunnedmedown meme was quite straightforward: to create their own versions, young blacks juxtaposed two photographs of themselves, one fitting the media stereotype of the “thug” and the other showing a conventionally “proper” appearance in the eyes of mainstream society (in graduation robes, military uniforms, etc.). The campaign thus critiqued the way in which black victims of police violence like Michael Brown are negatively depicted in the news media, and furthermore worked to expand and reframe the visual representation of young black men and women in the public sphere. #iftheygunnedmedown was only a small piece of the broader social media activity surrounding the #blacklivesmatter movement, yet it most acutely demonstrates how networked digital platforms in fostering unique and innovative modes of grassroots political expression.

This sort of hashtag-as-participatory meme popped time and time again in the online political discourse of 2014. Another example used in conjunction with #blacklivesmatter, #crimingwhilewhite (in which whites offered testimonials of their own privileged treatment when dealing with police), proved to be a source of controversy within the movement. The tactic was also employed repeatedly in the course of feminist online activism, another major viral politics story of 2014. In particular #yesallwomen and #whyistayed both worked to incorporate women’s personal testimonies into larger feminist advocacy efforts, epitomizing the emergent hashtag-as-meme trend. #yesallwomen was actually a response to another hashtag, #notallmen, which has been used to critique feminist arguments about the widespread nature of misogyny in society; both appeared in the aftermath of the May 2014 mass shooting in La Isla, California, perpetrated by a young man who was apparently inspired by his hatred towards women. #yesallwomen became a venue for women to share personal stories about their experiences with sexism, misogyny and the threat of gender-based violence, bringing visibility to the issue one tweet at a time. In a similar fashion, #whyistayed grew out of another high-profile violent incident in the news (involving professional football player Ray Rice’s assault on his wife), and provided an opportunity for women to collectively share stories about domestic violence in order to shine a public light on this often-ignored problem.

What I find particularly interesting about #yesallwomen and #whyistayed (as well as #iftheygunnedmedown and #crimingwhilewhite) is how they use major news stories as springboards for addressing how the larger issues at stake affect the lives of individuals throughout the society. Rather than just spreading awareness or showing support or solidarity for a cause, they seek to expand the narratives and conversations surrounding political issues and provide ways of systematically linking them to the experiences of everyday citizens. This seems to me to be one of the most important aspects of viral politics more broadly: how social media and participatory culture can be used to make the personal political—and the political personal. Indeed, the many hashtag campaigns popularized in 2014 look to be a major step in this direction.