I’m very excited to announce that my new book, The Citizen Marketer: Promoting Political Opinion in the Social Media Age, is now available from Oxford University Press! I’ve also launched a new website for the book, www.citizenmarketer.org, which includes a blog where I’ll be posting in the future on relevant social media and politics topics. Since I’m putting all my effort behind the new site, I won’t be updating this blog as much anymore, although I invite you to check out the archive here for posts covering 2013-2016.

Here’s a short summary of the new book:

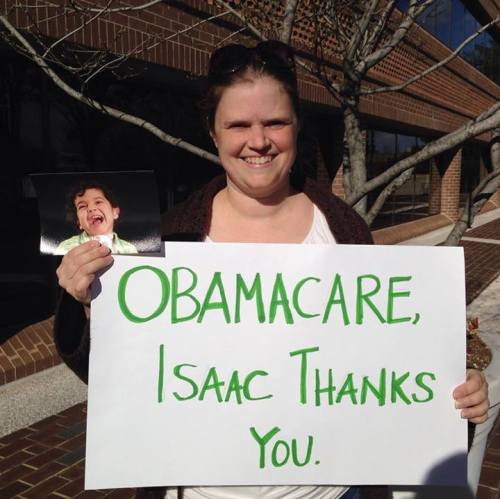

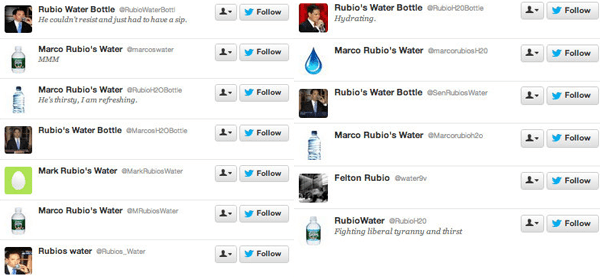

From hashtag activism to the flood of political memes on social media, the landscape of political communication is being transformed by the grassroots circulation of opinion on digital platforms and beyond. By exploring how everyday people assist in the promotion of political media messages to persuade their peers and shape the public mind, Joel Penney offers a new framework for understanding the phenomenon of viral political communication: the citizen marketer. Like the citizen consumer, the citizen marketer is guided by the logics of marketing practice, but, rather than being passive, actively circulates persuasive media to advance political interests. Such practices include using protest symbols in social media profile pictures, strategically tweeting links to news articles to raise awareness about select issues, sharing politically-charged internet memes and viral videos, and displaying mass-produced T-shirts, buttons, and bumper stickers that promote a favored electoral candidate or cause. Citizens view their participation in such activities not only in terms of how it may shape or influence outcomes, but as a statement of their own identity. As the book argues, these practices signal an important shift in how political participation is conceptualized and performed in advanced capitalist democratic societies, as they casually inject political ideas into the everyday spaces and places of popular culture.

While marketing is considered a dirty word in certain critical circles — particularly among segments of the left that have identified neoliberal market logics and consumer capitalist structures as a major focus of political struggle — some of these very critics have determined that the most effective way to push back against the forces of neoliberal capitalism is to co-opt its own marketing and advertising techniques to spread counter-hegemonic ideas to the public. Accordingly, this book argues that the citizen marketer approach to political action is much broader than any one ideological constituency or bloc. Rather, it is a means of promoting a wide range of political ideas, including those that are broadly critical of elite uses of marketing in consumer capitalist societies. The book includes an extensive historical treatment of citizen-level political promotion in modern democratic societies, connecting contemporary digital practices to both the 19th century tradition of mass political spectacle as well as more informal, culturally-situated forms of political expression that emerge from postwar countercultures. By investigating the logics and motivations behind the citizen marketer approach, as well as how it has developed in response to key social, cultural, and technological changes, Penney charts the evolution of activism in an age of mediatized politics, promotional culture, and viral circulation.